Mission San Joseph de Escambe, ca. 1741-1761

Back to Pensacola Colonial Frontiers Project Page

See also: Mission Provinces of Spanish Florida / Document Transcriptions

During the summer of 2009, members of a University of West Florida archaeological field school searched for and discovered an archaeological site that appears to be the long-lost remains of Mission San Joseph de Escambe. This mission is the original namesake for the Escambia River along which the site is located, and also for Escambia County, Florida. Although the burned ruins of this site were still visible during the 1770s, and were known to early British travelers and settlers in the area, memory of the mission's location and identity was largely lost by the time the region was permanently settled during the 19th century. Detailed historical and archaeological work carried out as a part of the Pensacola Colonial Frontiers Project have resulted in the identification of the 250-year-old archaeological site on private land in Molino, Florida, and archaeological research is still ongoing in order to learn more about the site and its inhabitants (see the 2009-2025 fieldschool blog, as well as online papers and reports for the project).

During the summer of 2009, members of a University of West Florida archaeological field school searched for and discovered an archaeological site that appears to be the long-lost remains of Mission San Joseph de Escambe. This mission is the original namesake for the Escambia River along which the site is located, and also for Escambia County, Florida. Although the burned ruins of this site were still visible during the 1770s, and were known to early British travelers and settlers in the area, memory of the mission's location and identity was largely lost by the time the region was permanently settled during the 19th century. Detailed historical and archaeological work carried out as a part of the Pensacola Colonial Frontiers Project have resulted in the identification of the 250-year-old archaeological site on private land in Molino, Florida, and archaeological research is still ongoing in order to learn more about the site and its inhabitants (see the 2009-2025 fieldschool blog, as well as online papers and reports for the project).

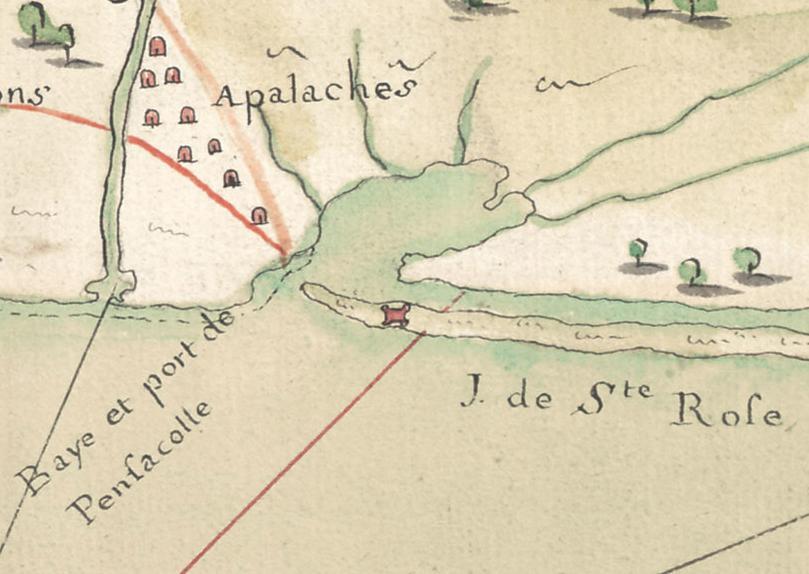

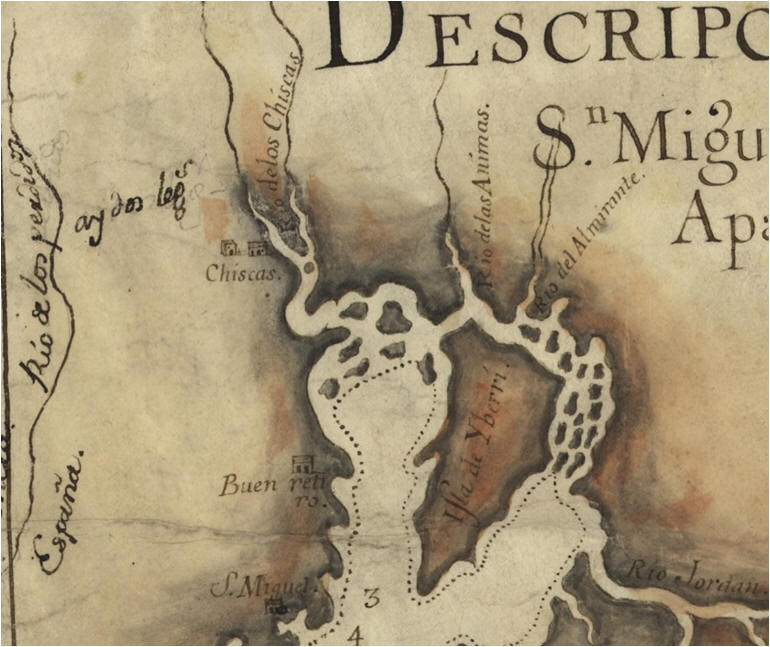

Documentary evidence indicates that the mission was certainly inhabited during the 1750s, and was likely founded in 1741. The river on which the mission was located had been known as the Rio de los Chiscas since the late 17th century, in reference to a much earlier Southeastern Indian group that had settled in West Florida during the last half of the 17th century. In 1741, a new mission community was established by Fray Marcos de Hita using funds allocated to Presidio Isla de Santa Rosa (1722-1756), and its name, "Nuevo Pueblo de los Chiscas," almost certainly refers to the fact that it was a new town established along the Chiscas River (the modern Escambia). The appearance of a town labeled "Chiscas" along the west bank of this river in the adjacent map (see right) would seem to support this hypothesis. While the identity of the 30 original residents of the town are not specified, later evidence confirms that the town was principally inhabited by Apalachee Indians under the Apalachee chief Juan Marcos Fant, who had established an earlier town near the mouth of the same river in 1718. Not long after the 1740 English seige on St. Augustine, a group of Yamasee Indians there had moved west to settle near Pensacola, and so the establishment of a new Apalachee town farther up the river may have been one reaction to the arrival of these new Yamasee refugees (who eventually formed the Punta Rasa mission near Garcon Point).

Documentary evidence indicates that the mission was certainly inhabited during the 1750s, and was likely founded in 1741. The river on which the mission was located had been known as the Rio de los Chiscas since the late 17th century, in reference to a much earlier Southeastern Indian group that had settled in West Florida during the last half of the 17th century. In 1741, a new mission community was established by Fray Marcos de Hita using funds allocated to Presidio Isla de Santa Rosa (1722-1756), and its name, "Nuevo Pueblo de los Chiscas," almost certainly refers to the fact that it was a new town established along the Chiscas River (the modern Escambia). The appearance of a town labeled "Chiscas" along the west bank of this river in the adjacent map (see right) would seem to support this hypothesis. While the identity of the 30 original residents of the town are not specified, later evidence confirms that the town was principally inhabited by Apalachee Indians under the Apalachee chief Juan Marcos Fant, who had established an earlier town near the mouth of the same river in 1718. Not long after the 1740 English seige on St. Augustine, a group of Yamasee Indians there had moved west to settle near Pensacola, and so the establishment of a new Apalachee town farther up the river may have been one reaction to the arrival of these new Yamasee refugees (who eventually formed the Punta Rasa mission near Garcon Point).

Documentary evidence regarding Mission Escambe's early years have yet to be identified, but considerable documentation is available for the period during the Seven Years War (1756-1763). Following long-distance negotiations between the English-allied Upper Creek Indians (in the vicinity of Montgomery, Alabama and northward) and Spanish-allied Yamasee and Apalachee leaders from the two Pensacola-area missions of Punta Rasa and Escambe, a general peace treaty between Creek and Spanish leaders was signed in Pensacola on April 14, 1758. In its aftermath, two new Creek towns were established within Spanish Florida by the spring of 1759, one of which was located just a few leagues upriver from Mission Escambe. At about the same time, Pensacola Governor Miguel Roman de Castilla y Lugo decided to send half of the new Spanish cavalry company to be garrisoned in Escambe, including fifteen men and an officer. The stated reason for this move was to pasture the horses in a better location, and to block the escape of Spanish fugitives northward from the Pensacola presidio, though the new garrison undoubtedly also provided a more effective out-guard and sentinel post along the Creek-Spanish frontier. The garrison was established no later than early 1760, and for the next year and a half, the Apalachee mission village of Escambe was also home to a formal garrison of Spanish soldiers.

In 1761, Spanish-Creek relations deteriorated precipitously, in part due to abuses by the officer in charge of the Escambe garrison, Ensign Pedro Ximeno, whose illicit trading activities with visiting Creeks included watered-down liquor and abusive treatment of dissatisfied customers (see details in the selection of translated documents). Despite a February 12 Creek assault on the Punta Rasa mission at Garcon Point, in which a Spanish infantry leader and virtually his entire family were murdered along with two other soldiers, the Escambe garrison was nonetheless maintained along the northern edge of Spanish control through spring. On April 9, however, a night-attack by 28 Creek warriors resulted in the destruction of the entire Escambe mission village, the murder of two soldiers, the scalping of a third, and the capture of four others, along with the plunder of seven horses and assorted weapons, munitions, and other equipment. In the aftermath, the Apalachee residents of Mission Escambe retreated southward to the vicinity of modern Pensacola, where they joined the previously-relocated Yamasee fugitives from Punta Rasa immediately adjacent to the Spanish fort (see 1765 image of still-standing structures in "Indian Town," to left). Despite the subsequent 1761 peace treaty ending hostilities, the mission refugees remained next to the Spanish fort, and just two years later, the 108 inhabitants of this combined Yamasee-Apalachee refugee community voluntarily evacuated Pensacola with the Spanish, eventually settling near Veracruz, Mexico, where some of their distant descendants might still live.

In 1761, Spanish-Creek relations deteriorated precipitously, in part due to abuses by the officer in charge of the Escambe garrison, Ensign Pedro Ximeno, whose illicit trading activities with visiting Creeks included watered-down liquor and abusive treatment of dissatisfied customers (see details in the selection of translated documents). Despite a February 12 Creek assault on the Punta Rasa mission at Garcon Point, in which a Spanish infantry leader and virtually his entire family were murdered along with two other soldiers, the Escambe garrison was nonetheless maintained along the northern edge of Spanish control through spring. On April 9, however, a night-attack by 28 Creek warriors resulted in the destruction of the entire Escambe mission village, the murder of two soldiers, the scalping of a third, and the capture of four others, along with the plunder of seven horses and assorted weapons, munitions, and other equipment. In the aftermath, the Apalachee residents of Mission Escambe retreated southward to the vicinity of modern Pensacola, where they joined the previously-relocated Yamasee fugitives from Punta Rasa immediately adjacent to the Spanish fort (see 1765 image of still-standing structures in "Indian Town," to left). Despite the subsequent 1761 peace treaty ending hostilities, the mission refugees remained next to the Spanish fort, and just two years later, the 108 inhabitants of this combined Yamasee-Apalachee refugee community voluntarily evacuated Pensacola with the Spanish, eventually settling near Veracruz, Mexico, where some of their distant descendants might still live.

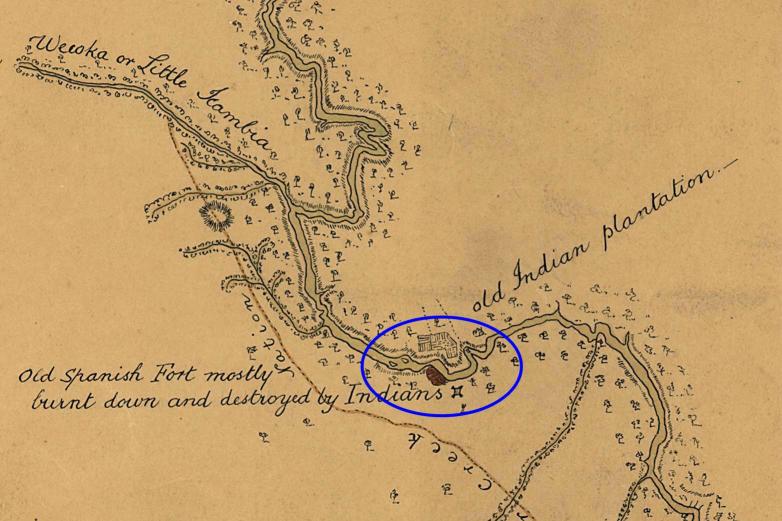

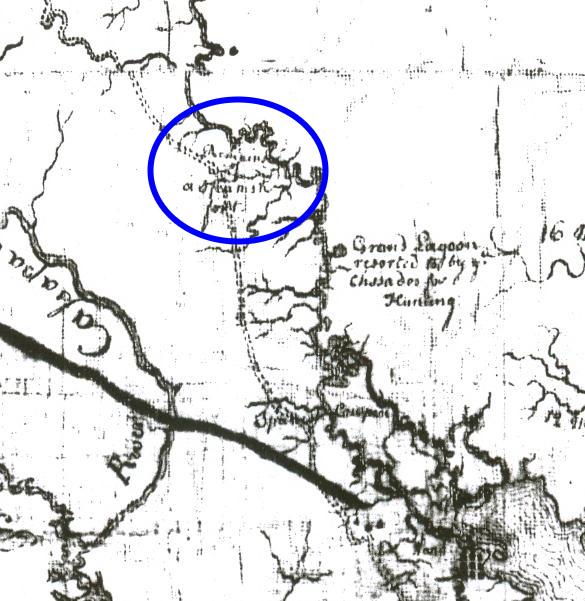

When British traders and settlers first began to travel up and down the Escambia River drainage as a primary corridor of travel and trade between British Pensacola and the Upper Creeks, they soon became aware of the burned ruins of Mission Escambe alongside the river. Several maps and text descriptions from the 1770s and 1780s make explicit note of what was interpreted as a "Spanish fort" in this location. Since Spanish descriptions of the location of the Escambe mission are remarkably consistent with later British maps and accounts, the British description of the burned "fort" undoubtedly refers to the garrisoned mission village, including not only the cavalry barracks with its stockaded compound but also the ruined church and other residential dwellings. Creek Indian informants doubtless remembered the presence of the stockaded Spanish cavalry garrison at the location, so British observers referred to the site as a fort, even though its defenses were relatively insubstantial, as the rapid destruction of the village makes obvious.

When British traders and settlers first began to travel up and down the Escambia River drainage as a primary corridor of travel and trade between British Pensacola and the Upper Creeks, they soon became aware of the burned ruins of Mission Escambe alongside the river. Several maps and text descriptions from the 1770s and 1780s make explicit note of what was interpreted as a "Spanish fort" in this location. Since Spanish descriptions of the location of the Escambe mission are remarkably consistent with later British maps and accounts, the British description of the burned "fort" undoubtedly refers to the garrisoned mission village, including not only the cavalry barracks with its stockaded compound but also the ruined church and other residential dwellings. Creek Indian informants doubtless remembered the presence of the stockaded Spanish cavalry garrison at the location, so British observers referred to the site as a fort, even though its defenses were relatively insubstantial, as the rapid destruction of the village makes obvious.

In addition to the Taitt map of 1771, and the Romans map of 1773 (selections shown here), brief mentions of this "Spanish fort" also appear in published British narratives. Thomas Hutchins (1784) noted the "old stockaded fort" nearly opposite a British plantation owned by William Marshall located on a large island in the river, and Bernard Romans (1773) asserted that "on the banks of this river, on an eminence, are the remains of a Spanish out-guard, or stocado fort." Both texts indicate that the fort was located some twenty-eight miles by road from Pensacola, and forty miles by water. Combined with the map evidence above, as well as earlier Spanish descriptions, these accounts provided substantial guidance in locating a target area for archaeological survey during the summer of 2009 along the Escambia River in the modern community of Molino, Florida. While no archaeological evidence for the mission community had previously been identified in this area, systematic survey by UWF students this summer confirmed the details from British and Spanish documentary sources, and provided the remarkable opportunity to conduct targeted archaeological investigations of this garrisoned Apalachee mission community from the mid-18th century.

In addition to the Taitt map of 1771, and the Romans map of 1773 (selections shown here), brief mentions of this "Spanish fort" also appear in published British narratives. Thomas Hutchins (1784) noted the "old stockaded fort" nearly opposite a British plantation owned by William Marshall located on a large island in the river, and Bernard Romans (1773) asserted that "on the banks of this river, on an eminence, are the remains of a Spanish out-guard, or stocado fort." Both texts indicate that the fort was located some twenty-eight miles by road from Pensacola, and forty miles by water. Combined with the map evidence above, as well as earlier Spanish descriptions, these accounts provided substantial guidance in locating a target area for archaeological survey during the summer of 2009 along the Escambia River in the modern community of Molino, Florida. While no archaeological evidence for the mission community had previously been identified in this area, systematic survey by UWF students this summer confirmed the details from British and Spanish documentary sources, and provided the remarkable opportunity to conduct targeted archaeological investigations of this garrisoned Apalachee mission community from the mid-18th century.

References Cited

Hutchins, Thomas

1784 An Historical Narrative and Topographical Description of Louisiana and West-Florida. R. Aitken, Philadelphia. [see also here]

Romans, Bernard

1776 A Concise Natural History of East and West Florida. R. Aitken, New York.