The Settlement of Spanish Florida

See also: Presidios of Spanish Florida / Missions of Spanish Florida / Florida After 1763

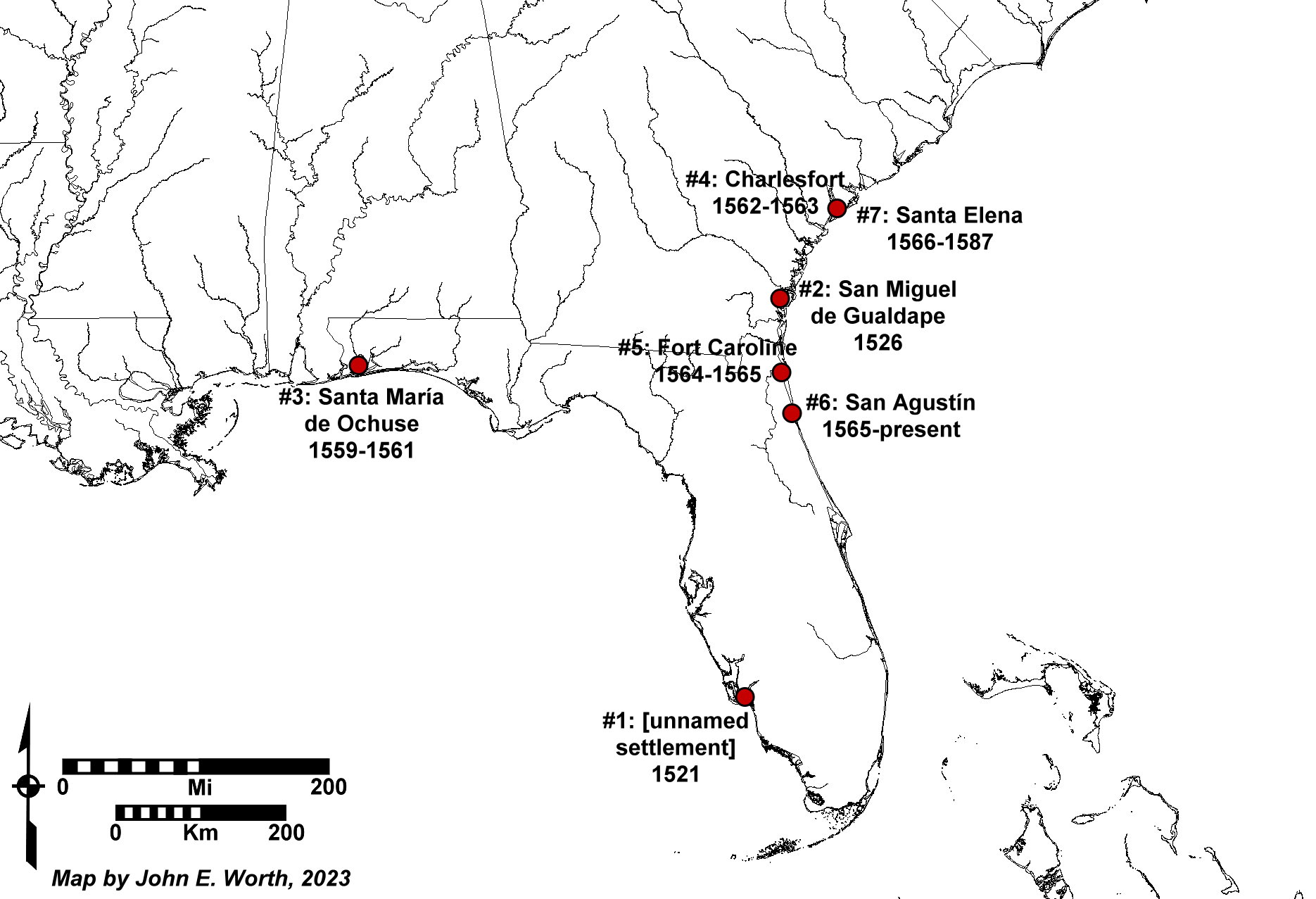

There were many failed attempts by Europeans to explore and settle the Southeastern United States between 1513 and 1565. Immediately below is a simple sequential list of the actual settlements attempted through the era of Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, who was the first to succeed by founding St. Augustine in 1565, and immediately below that is a more comprehensive descriptive list of all the major documented European expeditions launched either to explore or settle in what would later become the colony of Spanish Florida. For a map showing selected locations from the expeditions and settlements below, see the maps on the Places page.

At the bottom of the page, I've placed a list of links to online original-language accounts of many of these expeditions, including manuscripts, published books, transcripts, and also some online translations.

Settlements / Expeditions (Early / Late) / Accounts

List of Settlements

The sequential list below is limited to settlements that are documented actually to have been established on the ground by Spanish and French expeditions detailed in the next section below (links to the individual entries are provided). Not included in this list are expeditions that might ultimately have resulted in the establishment of settlements had the expeditions not failed (such as those of Pánfilo de Narváez, Hernando de Soto, or Luis Cancer), which are nonetheless detailed in the next section.

#1. [unnamed settlement] (Juan Ponce de León, 1521)

#2. San Miguel de Gualdape (Lúcas Vázquez de Ayllón, 1526)

#3. Santa María de Ochuse (Tristán de Luna y Arellano, 1559-1561)*

#4. Charlesfort (Jean Ribault, 1562-1563)*

#5. Fort Caroline (René de Laudonnière, 1564-1565)

#6. San Agustín de la Florida (Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, 1565-present)*

#7. Santa Elena (Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, 1566-1587)*

Note: Settlements indicated with an asterisk (*) have been identified archaeologically.

List of Expeditions

(see corresponding map here)

Juan Ponce de León, 1513

This exploratory expedition was sent from the island of Puerto Rico in search of the fabled island of Bimini, and accidentally resulted in the discovery of the landmass that Ponce named "Florida" in honor of the day of its discovery (Easter, or "Pascua Florida"). The expedition visited the middle and lower Atlantic coast of Florida, and rounded the Florida Keys to visit the Charlotte Harbor vicinity of Southwest Florida before returning to Puerto Rico. See original accounts below.

Pedro de Salazar, ca. 1514-1516

This exploratory expedition sailed the island of Hispaniola in search of new sources of American Indian slaves, and resulted in the capture of as many as 500 Native Americans from an island along the Atlantic coastline subsequently known as the "Island of Giants." Though few survived long after their return, the information gathered on this voyage set the stage for later Atlantic exploration.

Diego Miruelo, ca. 1516

This exploratory expedition is very poorly documented, but may have been launched from Cuba in search of slaves along the western coast of Florida. The expedition documented and named at least one large bay along the northern Gulf coastline, though several later expeditions had great difficulty in identifying it. The following year Juan Ponce de León was engaged in a lawsuit against Cuban governor Diego Velázquez del Cuellar for having allowed 300 Florida Indians to be captured and brought illegally to Cuba, and this might possibly have resulted from Miruelo's expedition.

Alonso Alvarez de Pineda, 1519

This exploratory expedition was sent by Jamaica governor Francisco de Garay in order to explore the coastline between Ponce de León's Florida and Hernán Cortés' New Spain (Mexico). The four-ship exploratory expedition charted the entire northern Gulf of Mexico, resulting in the first map showing the Gulf. The information gathered on this trip foreshadowed the subsequent expedition of Pánfilo de Narváez below.

This colonizing expedition was the first formal Spanish attempt to settle Florida, and involved a total of two ships with 200 colonists. The expedition landed somewhere in the vicinity of Fort Myers, Florida before being repulsed by a Calusa Indian attack which mortally wounded Ponce de León himself. Ponce withdrew the expedition and sailed to Cuba, where he died in the recently-established city of Havana. The expedition was abandoned thereafter.

Francisco Gordillo and Pedro de Quejo, 1521

This exploratory expedition was yet another Spanish slaving expedition which sailed northwest from the Bahamas (the two independent ships from Hispaniola joined forces after meeting in the Bahamas) in search of the land that Pedro de Salazar had discovered on his earlier slave raid. They captured some 60 slaves from the lower Atlantic coastline before returning to Hispaniola together.

Pedro de Quejo, 1525

This exploratory expedition was specifically dispatched by Lúcas Vázquez de Ayllón as a reconnaissance expedition for his planned colonial attempt to the Atlantic coastline visited earlier by Gordillo and Quejo. Quejo sailed along much of the eastern coast of North America before returning with extensive intelligence about this region.

This colonizing expedition was the second formal Spanish attempt to settle Florida, and involved six ships with 600 colonists. The expedition established the new town of San Miguel de Gualdape, possibly somewhere along the middle Georgia coastline, near the end of September. Nevertheless, Ayllón's subsequent death and a number of internal and external disputes doomed the colony to failure. The survivors fled by the end of October, though only a quarter of their number ever made it back to the Caribbean. See original accounts below.

Pánfilo de Narváez, 1528

This colonizing expedition was originally intended to settle along the northwestern Gulf coast just north of Cortés' New Spain colony, but severe storms drove the fleet to Tampa Bay on Florida's west coast, where the members of the expedition tried in vain to discover Diego Miruelo's bay, and eventually marched overland to the land of the Apalachee Indians at modern Tallahassee. From there, the expedition constructed improvised barges and attempted to skirt the northern Gulf coast toward northern Mexico, though most died along the way. Eight years later, Alvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca and three surviving companions finally reached Mexico City after wandering in an epic journey across the interior of Texas and northern Mexico. See original accounts below.

This exploratory expedition was designed to explore a broad region of southeastern North America in order to select the most suitable site for permanent settlement. Soto's expedition pushed rapidly inland toward the mountainous region that he hoped would produce riches on the same scale as his previous experience under Francisco Pizarro in Peru. The expedition sailed from Cuba with nine ships and about 600 people, mostly soldiers. Landing in Tampa Bay, the expedition seems to have followed Narváez's initial trajectory, marching inland and northward toward Apalachee. From there the expedition pushed deep into the interior Southeast, establishing an anticipated rendezvous point at Pensacola Bay for future resupply expeditions from Cuba. Repeated Cuban attempts to establish contact with Soto's lost expedition failed, while the expedition wandered for more than three years across much of eastern North America. Only half of the expedition's members ultimately survived to sail out the Mississippi River and along the Gulf coastline to Mexico. See original accounts below. See also the concurrent expeditions by Francisco de Maldonado below.

Francisco de Maldonado, 1539-1543

Maldonado's multiple expeditions started with an initial 1539-1540 reconnaissance expedition along the northern Gulf coast from St. Marks south of present-day Tallahassee, where Hernando de Soto's army wintered, Maldonado discovered the bay called Ochuse (Pensacola Bay), which was chosen as a rendezvous/resupply port for the Soto expedition. Maldonado was instructed to return with three ships loaded with supplies that fall, and he took a caravel and two bergantines to Pensacola during the fall-winter of 1540-1541, but found no trace or word from Soto's army. Additional exporations in the area had the same result, so Maldonado returned to Havana, and made two additional attempts to discover word of Soto in the summers of 1541 and 1542, followed by a final expedition in the spring of 1543, during which they finally received word along the western Gulf that survivors from Soto's expedition had reached Pánuco in northern New Spain.

This missionary expedition was as non-military as its predecessor had been military. Dominican missionary Fray Luís Cancer was granted permission to lead an expedition from Veracruz, Mexico consisting of four Dominican priests and one farmer in the attempt to establish a purely religious settlement along the Florida Gulf coastline, with the goal of spiritual conversion rather than military conquest. Though he cautioned the ship's pilot not to bring him near any place where Spaniards had already landed, the ship ultimately landed precisely where both Narváez and Soto had made landfall in the vicinity of Tampa Bay. Following the capture and murder of one priest and the farmer, Cancer himself was clubbed to death on the shore in sight of the ship, and the expedition withdrew in failure. See original accounts below.

Guido de Lavezaris, 1558

This reconnaissance expedition of three ships (a barca, fusta, and chalupa) was sent out from Veracruz on September 3 and explored the coastline of Mississippi and Alabama all the way to Mobile Bay, but was unable to continue eastward due to bad weather. The ships returned to Veracruz on December 14, and provided a report of their explorations.

Juan de Rentería, 1558-1559

This reconnaissance expedition is poorly documented, but consisted of a single ship that departed from Havana and apparently explored the northern Gulf coastline from at least Tallahassee to the Texas coast as part of preparations for the Luna expedition.

Tristán de Luna y Arellano, 1559-1561 (much more information provided on a separate page here)

This colonizing expedition was the first royally-financed colonial expedition to attempt the settlement of Florida, and also the first such colony to be staged from Mexico. With a total of eleven ships and 1,500 soldiers and colonists, it was also the largest to date. The expedition's ultimate goal was to head off an anticipated French settlement by establishing a Spanish colony at Santa Elena along the modern South Carolina coast (originally visited and named in the leadup to the Ayllón debacle). However, the strategy adopted was first to establish a colonial town along the northern Gulf coast at modern Pensacola Bay (then called Ochuse), and push inland to the famed Native American chiefdom of Coosa visited by the Soto expedition, and finally eastward to Santa Elena on the Atlantic coast. Only five weeks after landing, however, the expedition's fleet (and much of it's food onboard) was devastated by a hurricane, and the next two years were marked by attempts to stave off starvation, including the relocation of the bulk of the colonists inland to central Alabama, the dispatch of soldiers to Coosa in northwest Georgia in search of food, and multiple resupply expeditions from Veracruz. Most of the colony departed by the time Luna's replacement Angel de Villafañe sailed for Havana and Santa Elena in 1561, but the last remnants were finally withdrawn following the return of the failed Villafañe expedition below. See original accounts below.

Angel de Villafañe, 1561

This exploratory expedition departed from Havana with four ships and about 100 men (not counting an additional ship that sailed later), and briefly explored along the Atlantic coast in the vicinity of Santa Elena, in fulfillment of the original order for the Luna expedition. Beset by storms that sank two of the ships, the expedition failed to leave a Spanish presence at Santa Elena.

This first French exploratory expedition to Florida contained three ships cruised along the Florida, Georgia, and South Carolina coastlines before leaving a small garrison of 28 men in the newly-constructed Charlesfort at Santa Elena (Parris Island). The fort was abandoned in 1563 when the survivors decided to return to France. See original accounts below.

Hernando Manrique de Rojas, 1564

This Spanish exploratory expedition was sent north from Cuba in search of evidence of the rumored French settlement, and cruised the Georgia and South Carolina coast during the summer before finding the ruins of Charlesfort at Santa Elena, along with a sole French survivor who would later act as an interpreter for Spanish settlers.

René de Laudonnière, 1564-1565

This French colonial expedition established a garrisoned fort near the mouth of the St. Johns River near modern Jacksonville, Florida, where Jean Ribault had visited two years previously. Three ships containing some 300 men landed in June, quickly constructing Fort Caroline along the river. Over the course of the next year, the colony interacted extensively with surrounding Native Americans, but lack of supplies left them in a precarious position by the time an English fleet traded badly-needed supplies for most of the French cannons. When French supplies and reinforcements finally arrived under Jean Ribault in August, Spanish forces under Pedro Menéndez had already landed to the south, ultimately leading to the annihilation of the French colony. See original accounts below.

Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, 1565

The final (and only successful) Spanish expedition to colonize Florida was financed by both royal and private funds, and was led by Pedro Menéndez de Avilés. Five ships and some 800 soldiers and colonists arrived along the northeast coast of Florida in late August, where they ultimately slaughtered much of the French colonial force before establishing St. Augustine, which would become the first permanent European colonial city in Florida. From this port and administrative center, colonial Spanish Florida would grow over the course of the following decades, up to and including the short-lived Spanish town of Santa Elena (1566-1587) and three-succesive Veracruz-based Spanish presidios at Pensacola Bay (after 1698). See original accounts below.

Juan Pardo, 1566-1568

As part of Pedro Menéndez's initial thrust of exploration and settlement, he dispatched one of his recently-arrived company captains named Juan Pardo to lead half of his 250-man company at Santa Elena into the interior in an effort to fulfill the original mandate that had been given to Tristán de Luna y Arellano for his 1559-1561 expedition, to establish an overland route between the silver mines of northern New Spain and the Atlantic coast at Santa Elena. Turning back due to the start of winter at the Appalachian foothill town of Joara in western North Carolina, where he left a small garrison in newly-constructed Fort San Juan, Pardo returned in 1567 and pushed across the Appalachian summit before turning back again upon reports of a planned Native ambush. All the forts he established were overrun and destroyed by the spring of 1568, leaving the objective unfulfilled. See original accounts below.

(see corresponding map here)

Pedro de Chozas, 1597

As part of the growing Franciscan missionary effort in Florida, in 1597 Fray Pedro de Chozas set out for the interior from the head town of the Guale mission province, named Tolomato, along with Fray Francisco de Verascola and soldier Gaspar de Salas, accompanied by 30 Guale Indians under Tolomato's chief don Juan. The group traveled to the provinces of Tama and Ocute before turning back and taking a different route to mission San Pedro on Cumberland Island.

Juan de Lara, 1602

In 1602, Governor Gonzalo Méndez de Canzo dispatched another soldier, Juan de Lara, to return to Tama because of rumors of foreigners in the deep interior, leading another group of Guale Indians. Lara pushed 20 leagues beyond Tama and Ocute before returning.

Adrián de Cañizares, 1625

Following two poorly documented expeditions sent to an unknown location in the interior by Florida Governor Juan de Salinas in 1624, in 1625 incoming Governor Luis de Rojas y Borja sent ensign Adrián de Cañizares as head of a party dispatched to investigate rumors of white horsemen in the norther interior, thought potentially to have originated among the recently-established English colonists along the Atlantic coast far to the north. Cañizares reached as far as the province of Tama before returning.

Pedro de Torres, 1627-1628

In 1627, Governor Luis de Rojas y Borja mounted an even larger expedition to investigate the rumors of white horsemen, sending ensign Pedro de Torres as head of a party of 10 Spaniards and 60 Indians under cacique don Pedro de Ybarra. They made two successive expeditions, with the second finally reaching as far north as the famed province of Cofitachequi, last visted during the Juan Pardo expeditions.

Expedition Accounts Online

The links below provide easy access to original-language documentary accounts of the early European exploration and colonization of Florida, focusing on the 16th century. When possible and available, I have provided links to original handwritten manuscripts, but most links are either to colonial-era published books or more recent published transcripts, with a few online English translations as well.

Ponce de León / Ayllón / Narváez / Soto / Cancer / Luna / Ribault-Laudonniere / Menéndez / Pardo

Later European expeditions: Hilton / La Salle / "Classic" Spanish Expedition Accounts

Juan Ponce de León Expeditions

Original Published Book

Herrera de Tordesillas (1601): A secondary historical account published by the royal historian nearly eight decades after the 1513 Ponce de León expedition, but apparently based on direct access to an original log of the expedition, which has since disappeared.

Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés (1853): A secondary historical account originally penned in the 1540s, but not published in print until the 1850s, based on information about the Ponce de León expeditions from a generation later. The sections discussing the expeditions are indicated below.

V. 1 (1851), p. 482 / V. 1 (1851), p. 486 / V. 3 (1853), pp. 621-623

Lúcas Vázquez de Ayllón Expedition

Published Transcriptions

Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés (1853, 1855): A secondary historical account originally penned in the 1540s, but not published in print until the 1850s, based on interviews with survivors of the Ayllón expedition. The sections discussing the Ayllón expedition are indicated below.

Original Manuscript

Cabeza de Vaca (after 1537): An early handwritten account of the Narváez expedition by its royal treasurer, occupying just four folios of text. Considerably less detailed than its author’s later published account (below), and includes much of the same information.

Published Transcriptions

Cabeza de Vaca (1542): A lengthy and now famous account published by the royal treasurer of the Narváez expedition, one of its only four survivors who wandered back into New Spain eight years after being stranded on the Florida Gulf coast. The Florida section comprises only a portion of his long narrative.

Cabeza de Vaca (1555): Second edition, with parallel translation online; see description above. Another complete copy with only handwritten text for the first few pages that are missiong the printed text is available here, and a partial scan of a different print of the same edition is located here.

Cabeza de Vaca (1749): A later transcript as part of a collection of documents; see description above.

Cabeza de Vaca (1906): A later transcript as part of a collection of documents; see description above.

Published Translations

Cabeza de Vaca (Bandelier 1904 transation): See description above.

Cabeza de Vaca (Favata and Fernández 1993 translation): Presented parallel to the 1555 edition described above.

Original Manuscript

Biedma (c1544): A brief but important account written shortly after the return of the expedition by the royal factor; the only Soto expedition account for which the original manuscript remains.

Cañete (1565) (Image 381, or Bloque 10, Image 15-16): An extremely brief summary of testimony said to have been taken from two survivors of the Soto expedition, "Fray Sebastián de Cañete and the captain," penned by public notary Rodrigo Ramírez in San Juan, Puerto Rico, as part of Pedro Menéndez's paperwork relating to his contract to settle Florida.

Original Published Book

Elvas (1557): A detailed account authored by an anonymous Portuguese survivor of the Soto expedition. Similar in many ways to the earlier Ranjel account published by Oviedo, but including other details, and covering the entirety of the expedition.

Garcilaso (1605): A lengthy novelesque narrative of the expedition written by the Inca Garcilaso as a secondary historical account of the Soto expedition, but including information from firsthand interviews with survivors and from now-lost manuscript accounts. See also the digitized examples of the 1723 reprint of this volume here and here (in part since at least a few of the pages appear to be missing or misplaced in the 1605 edition scan).

Published Transcriptions

Biedma (1865): See description above.

Ranjel (1851: 544-577): A detailed account first published by royal historian Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés shortly after the Soto expedition during the 1540s, substantially drawn from the personal diary of Soto’s secretary Rodrigo Ranjel, but including inserted editorial comments from Oviedo. Considered the most reliable account as to day-by-day activities, but lacking the last part of the expedition. The original manuscript from which this was drawn is located in the Real Academia de la Historia as manuscript 9-553 (also 9-4-1-H-30), as shown in its catalog (see p. 125).

Elvas (1844): See above.

Published Translations

The Discovery and Conquest of Terra Florida by Don Ferdinando de Soto and Six Hundred Spaniards, His Followers (1851): Reprint of the 1611 English translation of the Elvas account.

History of the Conquest of Florida (1881): Barnard Shipp's English translation of a French translation by Pierre Richelet of the Garcilaso account.

Narratives of the Career of Hernando de Soto in the Conquest of Florida (v. 1) (1904): Bourne translation of the Elvas account.

Narratives of the Career of Hernando de Soto in the Conquest of Florida (v. 2) (1904): Bourne translations of Biedma and Ranjel accounts.

The DeSoto Chronicles (v. 1) (1993, snippet view only): Modern English translations of the Elvas (Robertson), Ranjel (Worth), Biedma (Worth), and Cañete (Lyon) accounts.

The DeSoto Chronicles (v. 2) (1993, snippet view only): Modern English translations of the Garcilaso (Shelby) account.

The DeSoto Chronicles (v. 1-2) (1993, with previews of selected portions).

Original Manuscript

Cancer/Beteta (1549): Detailed original handwritten manuscript diary composed by Fray Cancer himself through his murder, and subsequently completed by his second-in-command Fray Gregorio de Beteta.

Original Published Book

Dávila Padilla (1596): A detailed narrative of the Luna expedition originally published in 1596 as part of a voluminous history of the Dominican order in New Spain. The volume author attributed some of the text to previous authors, and internal evidence clearly indicates that this section of the Dávila Padilla was originally authored by Fray Domingo de la Anunciación, head of the Luna expedition missionaries after the departure of Fray Pedro de Feria following the 1559 hurricane. [another digitized copy here; 1625 edition here; 1634 version here; comparative pagination for Florida section below]

Chapter

1596

1625

Edición Segunda1634

Segunda ImpressiónLVIII. De la gente que por orden del Rey don Felipe fue a poblar la Florida, llevando religiosos desta provincia: y de su llegada al puerto.

231

189

231

LIX. De la terrible tormenta q[ue] destruyo las naos, y de las malas nuevas que huvo por tierra.

234

192

234

LX. De la vida del bienaventurado F[ray] Bartolome Matheos.

240

195

240

LXI. Del descubrimiento de Nanipacna, y de la grande hambre de la gente, antes y despues de llegar a ella.

242

198

242

LXII. De la entrada de dozientos soldados hasta Olibahali, co[n] grande trabajo, y del que Dios libro al P[adre] F[ray] Domingo de la Annunciacion diziendo Missa.

245

201

245

LXIII. Del ardid con que sacaron a los nuestros de su tierra, los de Olibahali, y de la llegada a la provincia de Coça.

248

204

248

LXIIII./LXIV. De como los Españoles favorecieron a los de Coça, contra los Napochies, y de algunas ceremonias que usavan estos Indios en sus guerras.

251

207

251

LXV. De las ceremonias con que los Cocenses prosiguieron su viaje hasta un pueblo que los Napochies desampararon: y lo que les sucedio en el.

256

210

256

LXVI. De como siguiendo el alcance los de Coça, se les rindieron los Napochies, y los Españoles se bolvieron a Coça.

261

214

261

LXVII. De como el real de los Españoles bolvio de Nanipacna al puerto, y los religiosos a Mexico: de donde se mando llevar socorrro a los de la Florida.

264

217

264

LXVIII. De como vino nueva de lo sucedido en Coça, y del principio que tuvo una dissension grande entre el Governador y su gente.

266

219

266

LXIX. De la venida de los dozientos soldados de Coça, y discurso de la discordia en el real de los Españoles.

270

222

270

LXX. De las milagrosas amistades que el P[adre] F[ray] Domingo de la Anunciacion hizo, confirmandolas Dios con el socorrro que el santo frayle avia profetizado.

272

224

272

LXXI. De un milagro que Dios obro multiplicando la harina en manos del bendito padre F[ray] Domingo de la Anunciacion, y de su venida a Mexico.

276

227

276

Published Transcriptions/Translations

The Luna Papers (v. 1) (1928): A collection of parallel Spanish transcriptions and English translations of many important previously unpublished documents relating to the Luna expedition, including litigation paperwork accumulated by Luna during the expedition and subsequently presented to the Council of the Indies in Spain, and many other letters, petitions, and testimony. Google Books version here.

The Luna Papers (v. 2) (1928): See above. Google Books version here.

Ribault/Laudonnière Expeditions

Original Published Books

Laudonnière (1586): Narrative accounts of three French voyages to Florida (1562 under Ribault, 1564-1565 under Laudonnière himself, and again under Ribault in 1565), authored in French by one of the few survivors who made it back to France after the Spanish arrived in 1565.

de Bry (1591): A publication that includes many famous engravings by Theodore de Bry based on now-lost paintings by Jacques Le Moyne de Morgue of the French colonial experience in Florida, with lengthy text captions in Latin. A high-resolution version of his contemporaneous map of Florida is available from the Library of Congress.

Published Facsimile

Ribault (1927): Facsimile edition of a 1563 English version of Ribault’s own report on his 1562 expedition to Florida.

Published Translations

Laudonnière (1600/1810): English translation by Richard Hakluyt republished as part of a later collection of narratives.

Laudonniere (1975; preview only): English translation by Charles Bennett.

Published Transcriptions

Solís de Merás (1893; another scan here): The first printed publication of a manuscript written by Pedro Menéndez de Avilés’ brother-in-law, including narrative accounts of the many coastal expeditions along the Atlantic and lower Gulf coasts of Florida during the late 1560s.

Published Translations

Solís de Merás (1923): English translation by Jeannette Thurber Connor.

Original Manuscripts

Pardo (1566): A brief handwritten account by Captain Juan Pardo himself describing his first expedition into the interior of the Carolinas during 1566-1567.

Bandera (Short Account) (1569): A brief summary of places visited by the Pardo expeditions, penned by notary Juan de la Bandera.

Bandera (Long Account) (1569): A transcript of a lengthy oficial notarial record of the second Pardo expedition, providing amazingly detailed descriptions of towns visited, chiefs met, gifts distributed, and testimony regarding the anti-Spanish plot led by the chief of Coosa.

Published Translations

Bandera (Long Account): An online scan of the Hoffman translation of this document, from volume below.

The Juan Pardo Expeditions (1990, snippet view only): The appendix to this book includes complete Spanish transcripts and English translations by Paul Hoffman of all major Pardo accounts.

Original Published Book

A Relation of a Discovery Lately Made on the Coast of Florida (1664), by William Hilton: An account of an early English expedition along the lower coast of modern South Carolina, including interactions with local Natives and Spanish missions to the south.

Top of SectionPublished Translations

The Journeys of Réné Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, by Isaac Joslin Cox: English translations of assorted accounts of the French expeditions to the Mississippi River and Gulf of Mexico under La Salle.

"Classic" Spanish Expedition Accounts

Historia General y Natural de las Indias, by Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés (original 16thC, first printed 1851-1855)

Vol. 1 (1851) / Vol. 2 (1852) / Vol. 3 (1853) / Vol. 4 (1855)

Historia General de las Indias (Vols. 1 & 2), by Francisco López de Gómara (1552)

Historia general de los hechos de los castellanos en las Islas i Tierra Firme del Mar Oceano, by Antonio de Herrera y Tordesillas(1601)

Historia General de las Indias Occidentales: Década IX. Continúa la de Antonio de Herrera De el año de 1555 hasta el de 1565, by Pedro Fernández del Pulgar (after 1689)

Historia Verdadera de la Conquista de la Nueva España, by Bernal Díaz del Castillo (1632), ed. by Genaro García (1904) (see also original handwritten version here; reprinted English translation from 1900 is here)