The Luna Settlement

Back to Main Luna Expedition Page

See also: Luna Fleet / Luna Documents / Luna Bibliography

In mid-December of 2015, the University of West Florida announced the discovery of the archaeological traces of the 1559-1561 terrestrial settlement of Tristán de Luna on the shore of Pensacola Bay, not far from the two shipwrecks that have long been under investigation as part of Luna's 1559 colonizing fleet, where UWF has been substantially involved in maritime research relating to the Luna expedition since the 1992 discovery of the Emanuel Point I wreck in Pensacola Bay, and especially after a second ship (called Emanuel Point II) was found nearby in 2006. With the generous permission and support of the many private landowners in the neighborhood where the Luna settlement is located, UWF spent most of 2016 conducting reconnaissance excavations in and around the site in order to determine the spatial extent and internal configuration of the site, and the degree of preservation of the underground archaeological deposits. Two sections of UWF's terrestrial summer field schools were conducted at the site in 2016, and another is underway in 2017. For the foreseeable future, I will be posting updates and information both here and on the project blog. For more information about the find, please refer to the following websites, which include the official UWF press page, and several online articles relating to the find:

In mid-December of 2015, the University of West Florida announced the discovery of the archaeological traces of the 1559-1561 terrestrial settlement of Tristán de Luna on the shore of Pensacola Bay, not far from the two shipwrecks that have long been under investigation as part of Luna's 1559 colonizing fleet, where UWF has been substantially involved in maritime research relating to the Luna expedition since the 1992 discovery of the Emanuel Point I wreck in Pensacola Bay, and especially after a second ship (called Emanuel Point II) was found nearby in 2006. With the generous permission and support of the many private landowners in the neighborhood where the Luna settlement is located, UWF spent most of 2016 conducting reconnaissance excavations in and around the site in order to determine the spatial extent and internal configuration of the site, and the degree of preservation of the underground archaeological deposits. Two sections of UWF's terrestrial summer field schools were conducted at the site in 2016, and another is underway in 2017. For the foreseeable future, I will be posting updates and information both here and on the project blog. For more information about the find, please refer to the following websites, which include the official UWF press page, and several online articles relating to the find:

UWF Main Page on Luna Settlement Discovery

"Luna's Colony Found in Pensacola"(Pensacola News Journal, 12/17/15)

"UWF, Community Partner to Study Our Past" (Editorial, Pensacola News Journal, 12/19/15)

Below is a peer-reviewed article and several short conference papers that I and co-authors have presented in the past five years discussing some preliminary observations regarding archaeological work at the Luna settlement site, including many illustrations and maps (for other published works on the Luna expedition, see the Luna bibliography page):

The Luna Settlement in Archaeological and Documentary Perspective. Paper presented in the symposium “Exploring the Settlement and Fleet of Tristán de Luna” organized by John E. Worth and John R. Bratten at the 37th Annual Gulf South History and Humanities Conference, Pensacola, Florida (2019). (program for entire symposium is here).

I also have a special page with more information about the Tristán de Luna expedition in general, including contextual maps locating the maritime and terrestrial routes followed by Luna's fleet and infantry and cavalry detachments.

Finally, I have also assembled a UWF Field Schools Crew Shot Gallery with group photos of all the students who participated in the terrestrial archaeological field schools I have taught since 2009, including those at the Luna Settlement from 2016 to present.

This page will be undergoing considerable expansion in coming months and years, so please check back for updates.

The Luna Settlement in Documentary Perspective

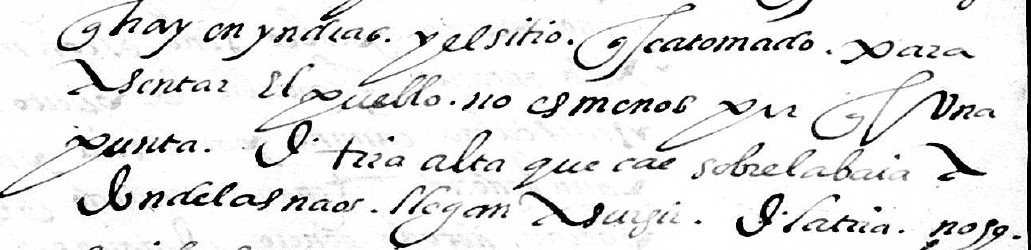

Tristán de Luna's terrestrial settlement was established not long after the arrival of the colonial fleet in Pensacola Bay on August 14-15, 1559. The location was described by Tristán de Luna himself as being located on “a point of high land that overlooks the bay where the ships arrive to anchor,” and by the Viceroy (summarizing reports from Luna) as “a very spacious port, which has three leagues in width in front of where the Spaniards are now,” where “the naos [large ships] can be anchored in 4 or 5 fathoms at one crossbow-shot from land.”

Tristán de Luna's terrestrial settlement was established not long after the arrival of the colonial fleet in Pensacola Bay on August 14-15, 1559. The location was described by Tristán de Luna himself as being located on “a point of high land that overlooks the bay where the ships arrive to anchor,” and by the Viceroy (summarizing reports from Luna) as “a very spacious port, which has three leagues in width in front of where the Spaniards are now,” where “the naos [large ships] can be anchored in 4 or 5 fathoms at one crossbow-shot from land.”

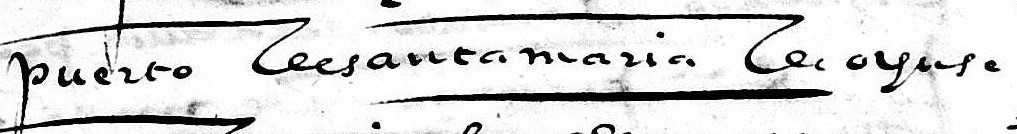

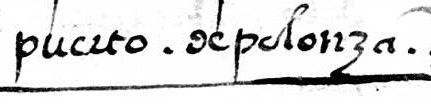

The port settlement was variously referred to in the documents as Santa María de Ochuse, or alternatively Polonza. The name Ochuse had been the indigenous name of the bay, as recorded by Hernando de Soto’s lieutenant Francisco Maldonado during his 1540 discovery of the Native American town and province by that name, followed by annual visits to the bay by ship from Havana seeking news of Soto’s whereabouts through 1543.

The port settlement was variously referred to in the documents as Santa María de Ochuse, or alternatively Polonza. The name Ochuse had been the indigenous name of the bay, as recorded by Hernando de Soto’s lieutenant Francisco Maldonado during his 1540 discovery of the Native American town and province by that name, followed by annual visits to the bay by ship from Havana seeking news of Soto’s whereabouts through 1543.

The settlement was initially inhabited by some 1,500 soldiers and colonists from New Spain, including up to 550 soldiers between infantry and cavalry, many of their families, servants and some African slaves, and 200 Aztec Indian warriors and craftspeople. The population of the Luna settlement never dropped below 50-100 inhabitants during its more than two-year duration, starting with 1,500 people in August of 1559, dropping to just 100 between February and July of 1560, when Luna led most of the settlers inland to an Indian town called Nanipacana, and then after their return ranging from perhaps 800 to less than 200 through April of 1561, when most of those left departed with Luna’s replacement governor Angel de Villafañe. A detachment of just 50-60 soldiers remained at the settlement until being withdrawn late in 1561.

The settlement was initially inhabited by some 1,500 soldiers and colonists from New Spain, including up to 550 soldiers between infantry and cavalry, many of their families, servants and some African slaves, and 200 Aztec Indian warriors and craftspeople. The population of the Luna settlement never dropped below 50-100 inhabitants during its more than two-year duration, starting with 1,500 people in August of 1559, dropping to just 100 between February and July of 1560, when Luna led most of the settlers inland to an Indian town called Nanipacana, and then after their return ranging from perhaps 800 to less than 200 through April of 1561, when most of those left departed with Luna’s replacement governor Angel de Villafañe. A detachment of just 50-60 soldiers remained at the settlement until being withdrawn late in 1561.

Although the hurricane that destroyed the fleet and the expedition's remaining food reserves never allowed Luna's Pensacola Bay settlement to reach the stage where the planned colonial town could be fully constructed, the 1573 Ordinances issued by the Spanish Crown nonetheless provide important insights into the mindset of mid-16th-century Spanish colonial authorities regarding the establishment of new colonial towns. They describe a sequence of construction that began with the establishment of a principal plaza and roads branching out from it (with a different layout for port towns than those inland), followed by the assignment of lots for public buildings alongside the plaza, starting with the church, followed by the town council house and other public port facilities, including commercial facilities to be constructed using tax revenue, all followed by the assignment of lots to individual settlers. Settlers were to erect tents or other temporary structures made using available materials, and then focus on sowing crops and placing livestock in order to generate food. Only after the food question had been resolved were the settlers to begin constructing more permanent houses on their lots.

Extracts from 1573 Ordinances

Translated by John E. Worth.Item #112: “The principal plaza where the settlement should be begun, being on the coast of the sea, should be made at the landing of the port, and being in the middle of the land, in the middle of the settlement. The plaza should be in an extended square which is in length at least one and a half times its width, because this shape is the best for the fiestas with horses, and whichever others that are to be done.”

Item #113: “The size of the plaza should be proportional to the quantity of the residents...and thus the selection of the plaza will be made with respect to [the fact] that the settlement could grow, it should not be less than two hundred feet in width and three hundred in length, nor greater than eight hundred feet in length...and a good proportion is six hundred feet in length and four hundred in width.”

Item #114: “From the plaza should issue four principal streets, one in the middle of each side of the plaza, and two streets from each corner of the plaza. The four corners of the plaza should face the four principal winds, because in this manner, since the streets come off the plaza, they are not exposed to the four principal winds, which would be of great inconvenience.”

Item #119: “For the temple of the principal church, if the settlement is on the coast, it will be built in a place that it can be seen upon going out to sea, and that its construction should be in defense of the same port.”

Item #120: “For the temple of the principal church, parish, or monastery, lots should be assigned, the first after the plaza and streets, and they should be in a complete block, in a manner that no building should come close to it, except those pertaining to its style and adornment.”

Item #121: “Next a site and place for the royal house of the council and cabildo, customs house, and dockyard next to the same temple and port, in a manner that in times of need they may all help each other. The hospital for the poor and those sick from diseases that are not contagious should be placed next to the temple and on its patio. For those sick with contagious diseases the hospital should be put in a place that no dangerous wind passing by it should go to damage the rest of the settlement, and if it can be built in an elevated place it will be better.”

Item #122: “The site and lots for butcher shops, fish markets, tanneries, and other things that generate filth will be put in a place where they can easily be maintained without filth.”

Item #126: “On the plaza, lots should not be given to private individuals, where for the construction of the church and royal houses and those owned by the city, stores and houses for merchants should be built, and these should be built first, for which all the settlers should contribute, and some moderate tax should be placed upon the merchandise so that they may be built.”

Item #128: “Having made the plan of the settlement and the distribution of the lots, each one of the settlers in his own [lot] should set up his tent [toldo], if he has one, for which the captains should persuade them to carry them, and those who do not have them should make their camp [rancho] from materials that can be obtained easily, where they may all gather, and everyone with the greatest promptness should make some palisade or trench around the plaza in a manner that they cannot receive damage from the native Indians.”

Item #132: “The settlers having sown [their seeds] and placed the livestock in such quantity and with such good diligence that they expect to produce an abundance of food, they should begin with great care and duty to establish their houses and build with good foundations and walls, for which they should go prepared with molds or boards to make them, and all the other tools to build with brevity and at little cost.”

Source of Spanish Transcription for Translation Above:

Nuttall, Zelia

1921 Royal Ordinances Concerning the Laying out of New Towns. The Hispanic American Historical Review 4(4): 743-753. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2505686