Colonial-Era Spanish Religion

This page in-development provides selected information on the religious practice of colonial-era Spaniards, specifically as regards how it affected daily life and material culture. Below are descriptions of liturgical texts and prayer books in-use during the era, as well as ecclesiastical rules for behavior framed within the Catholic liturgical calendar described on a separate page. More information regarding additional topics and time periods will be presented as time permits.

Liturgy and Prayers / Ecclesiastical Rules

Liturgy and Prayers

The principal liturgy of colonial-era Spanish Catholics was the Mass, which was of course the pre-modern Tridentine Mass after its promulgation by Pope Pius V in 1570, and before that the Roman Missal initially printed in Milan in 1474. Below are some links to digitized missals (all in Latin) that contain the liturgical texts that would likely have been used during Mass in colonial Spanish Florida.

- Missale Romanum (c1496-1497): An early missal that includes the Roman texts approved for use at the time of the earliest New World discoveries.

- Missale secundum ordinem fratrum Praedicatorum: Juxta Decreta Capituli Generalis, Anno Domini 1551 Salmantice celebrati, reformatum: & authoritate Apostolica comprobatum (1553): The Dominican missal likely to have been used by the Dominican missionaries on the Tristán de Luna y Arellano expedition.

- Missale romanum, ex decreto sacrosancti Concilij Tridentini restitum (1575): An early edition of the Tridentine Mass following 1570 revisions by Pope Pius V after the Council of Trent.

- Missale Romanum ex decreto Sacrosancti Concilij Tridentini restitutum (1623): A later edition of the Tridentine Mass following additional 1605 revisions by Pope Clement VIII.

- Missale Romanum ex decreto Sacrosancti Concilij Tridentini restitutum (1675): An even later edition of the Tridentine Mass following additional 1634 revisions by Pope Urban VIII.

- Novum Missale Romanum (1724)

- Missale Romanum (1759)

- Missae Propriae Sanctorum ad usum Fratrum Minorum Sancti Francisci Conventualium, Monialium Sanctae Clarae, ac Tertii Ordinis utriusque sexus (1763): A Franciscan missal including festivals particular to the Order of Friars Minor, who administered the Florida missions between 1574 and 1763.

A Spanish language translation from the colonial era is provided below, with extensive commentary:

An English language version from the colonial era is provided for comparison:

Detailed instruction manuals for saying Mass using the Roman Missal were published in Spanish during the same era, and an assortment of these are provided below, since they provide important supplements and summaries of the Mass text and official rubrics, including description of practices and actions during sacramental liturgies:

- Tractado muy vtil y curioso para saber bien rezar el Officio Romano, que divulgo Pio. V. P. Max. en el qual se declaran todas las rubricas generales, y particulares de el Breviario por su orden, como se vera en su Tabla (1584)

- Instruction para dezir missa conforme al Missal Romano, sacada en estylo claro del mismo Missal (1585)

- Ceremonial romano para missas cantadas y rezadas. En el quel se ponen todas las rubricas generales y particulares del missal romano, que diuulgo el papa Pio 5. con aduertencias y resoluciones de muchas dudas (1589)

- Ceremonial de los officios divinos: ansi para el altar, como para el choro, y fuera del, segun el uso de la Sancta Iglesia Romana, y conforme al Missal, y Breviario reformados por los Sanctissimos Pontifices Pio Quinto, y Gregorio decimo tercio (1591)

- Dudas acerca de las ceremonias sanctas de la Missa, resueltas por los clérigos de la Congregacion de nuestra Señora, fundada con authoridad Apostolica en el Collegio de la Compañia de IESUS de Mexico (1602)

- Ceremonial de la Missa: en el qual se ponen todas las Rubricas generales y algunas particulares del Missal Romano que divulgo Pio V, y mando reconocer Clemente VIII (1607)

- Ceremonial romano general: en el qual se ponen las ceremonias del coro, decretos de la Sacra Congregacion de Ritus, rubricas de D. Bartolome de Gauanto, oficio de la Semana Santa, oficio de Pontifical, y processiones, y otras cosas muy importantes, tocantes al oficio divino, para toda la Iglesia (1638)

- Ceremonial de las Misas: trata de las rubricas y ceremonias pertenecientes al Sacrosanto Sacrificio de la Misa y Ritos de la Semana Santa, conforme al Misal Romano de Pio V. Revormado por Clemente VIII. Y recognito por Urbano VIII (1647)

- Tratado de las Ceremonias de la Missa, y las demas cosas tocantes a ella, conforme al Misal Romano, ultimamente reformado por la Santidad de Clemente VIII (1655)

- Ceremonial romano de la missa rezada: conforme el missal mas moderno, con las avertencias de todo lo que se opone à las rubricas, para que con toda perfeccion se ofrezca el Santissimo Sacrificio de la Missa: y despues de sus ceremonias se ponen otros Documentos, y Reglas necessarias para todos los Sacerdotes (1695)

- Ceremonial Romano de la Missa Rezada (1726)

- Ceremonial Según las Reglas del Missal Romano (1753)

- Directorio de Sacrificantes: Instruccion Theoricopractica acerca de la Rubricas Generales del Misal, Ceremonias de la Misa Rezada, y Cantada, Oficios de Semana Santa, y de otros dias especiales del año (1769)

- Instruccion acerca de las Rubricas Generales del Misal, Ceremonias de la Misa Rezada y Cantada, Oficios de Semana Santa, y de otros dias especiales del año (1777)

- Instruccion sobre las Rúbricas Generales del Misal, Ceremonias de la Misa Rezada y Cantada, Oficios de Semana Santa, y de otros dias especiales del año (1797)

A detailed explanation of "the why of all the ceremonies of the Church and its mysteries" was published in 1760 and subsequent editions:

El Porqué de todas las ceremonias de la Iglesia y sus misterios: cartilla de prelados y sacerdotes, que enseña las ordenanzas ecclesiasticas, que deben saber todos los Ministros de Dios, by Antonio Lobera y Abio (Francisco Generas, Barcelona, 1760)

El Porqué de todas las ceremonias de la Iglesia y sus misterios: cartilla de prelados y sacerdotes que en forma de dialogo entre un vicario y un estudiante curioso, by Antonio Lobera y Abio (Imprenta de los Consortes Sierra y Marti, Barcelona, 1791)

Each priest was also obligated to recite a weekly series of prescribed daily prayers from the Roman Breviary, commonly known as the Divine Office, which was also keyed to the liturgical year. Two-volume sets began at Advent (winter) and Trinity Sunday (summer), while four-volume sets added divisions at Quadragesima Sunday (spring) and the first Sunday in September (fall). Below are links to a sampling of digitized breviaries (all in Latin) from the colonial era.

-

Breviarium Romanum (1542)

- Breviarium Romanum (1563)

- Breviarium Romanum (1570): A breviary postdating the major reform in the Roman breviary instituted by Pope Pius V in 1568.

- Oficia Propria Sanctorum Ordinis Minorum (1621): Breviary supplement specific to the Franciscan Order, including festivals particular to the Order (winter and summer volumes bound together).

- Breviarium Romanum, pars aestiva [summer] / pars hiemalis [winter] (1651)

- Breviarium Romanum...ad usum Fratrum & Sororum Trium Seraphici P. S. Francisci Ordinum (1708): A full breviary specific to the Franciscan order, including festivals particular to the Order.

- Breviarium Romanum (1714)

- Breviarium Romanum, pars hiemalis[winter], pars verna [spring], pars autumnalis [fall], pars aestiva [summer] (1829)

A detailed 17th-century explanation of the breviary and its use is provided in the Spanish language below:

An English language version from the colonial era is provided below for comparison:

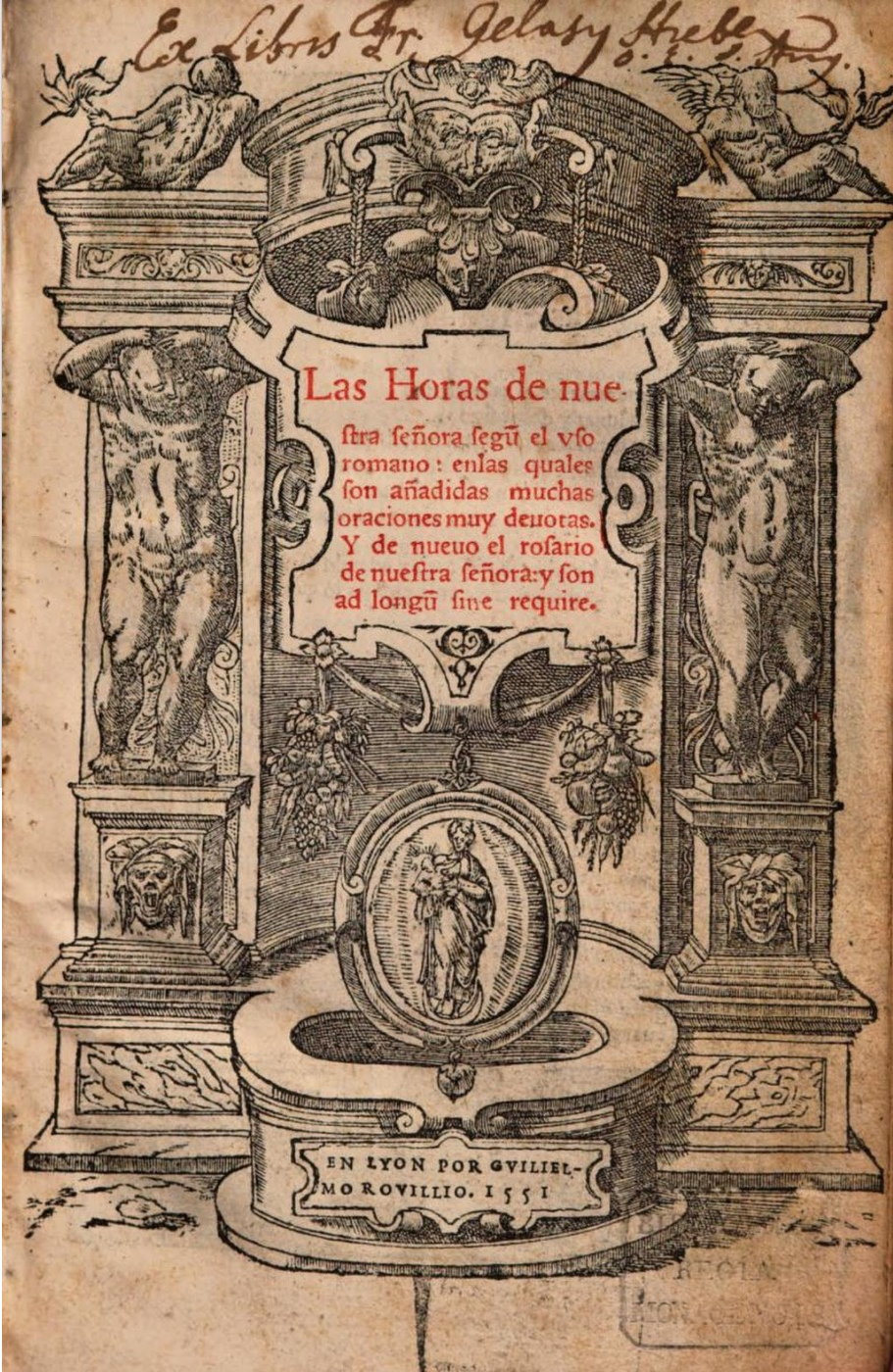

In the mid-16th century, during the era of Tristán de Luna y Arellano and Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, everyday Spaniards commonly made use of devotional prayer books dedicated to the Blessed Virgin Mary, or Our Lady. Probate records indicate that even poorer individuals with few possessions owned such books, usually in the Spanish language (Horas en Romance), but sometimes in Latin (Horas en Latin). Digitized examples of these books are linked below for this period.

- Las Horas de Nuestra Señora segun el uso Romano (1560): Spanish, simple format.

- Las Horas de Nuestra Señora segun el uso Romano (1551): Spanish, fancy format.

- Horae in Laudem Beatissimae Virignis Mariae, ad vsum Romanum (1549): Latin, simple format.

- Horae in Laudem Beatissimae Virignis Mariae, ad vsum Romanum (1549): Latin, fancy format.

Later examples of this "Oficio Parvo" or "Little Office" are below.

An English-language version from the colonial era is provided for comparison below:

Perhaps even more common in personal inventories were rosaries and strings of prayer beads, used as guides to prayer. Such beads were commonly made of wood, but were also fashioned from bone, jet, coral, crystal, jasper, amber, silver, and gold. Despite assumptions by many archaeologists, glass beads were not commonly used for rosaries, likely due to their fragility, but were instead most frequently noted as rescates (trade goods).

One of many contempory guides to praying the rosary can be found in the volume below, on folios 227-267.

Compilations of a wide range of ordinary personal religious practices and prayers for the laity are also illustrative of the religious dimension of daily life during the colonial era.

- Exercicio Quotidiano con Diferentes oraciones y devociones para antes y despues de la Confession y Sagrada Comunion, by Manuel Martín (Madrid, 1768)

- Exercicio quotidiano con diferentes oraciones para asistir con devocion al santo sacrifico de la Misa, y otras para antes y despues de la Confesion, y Sagrada Comunion, by "un devoto" (Madrid, 1795)

- Egercicio Quotidiano con Oraciones para la Misa, Confessión, Comunión, Via-Crucis, para todos los dias de la Semana, y otras de muchos Santos, &c., by Miguel and Tomás Gaspar (Barcelona, 1820)

Ecclesiastical Rules

Within the context of the broader Catholic liturgical calendar, Spanish Catholics were expected to confirm to specific rules of behavior with respect to behavior and diet. The information was below was compiled from a variety of sources, but is perhaps best summarized in the two-volume Instituciones del Derecho Canonico Americano, by Justo Donoso (1848-1849), esp. pp. 208-212 and 223-233.

On Sundays and major feast days throughout the year, the following activities were generally prohibited, with exceptions granted under specific circumstances:

- Servile Labor, including manual and intellectual labor, both obligatory and voluntary.

- Business Transactions, excluding the sale and purchase of necessities.

- Judicial Acts, including all stages of the judicial process.

In addition, below are the specific rules regarding abstinence from meat, as well as fasting (only one large meal in a day) combined with abstinence:

Abstinence (no meat)

- Fridays and Saturdays throughout the year

- Sundays in Lent only

- Major Rogation (Greater Litanies) on the day of St. Mark [April 25]

- Minor Rogations on the three days (Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday) preceding Ascension Thursday

Fasting and Abstinence (only one meal, and no meat)

- All days of Lent, excluding Sundays

- Wednesdays, Fridays, and Saturdays of the four Ember Weeks, including (1) the week after the first Sunday of Lent, (2) the week after Pentecost, (3) the week after Exaltation of the Cross [Sept. 14], (4) the last full week before the Christmas Vigil [Dec. 24]

- Vigils (excluding Sundays, when fast is observed the previous Saturday), including vigils for the feast days of Christmas, Pentecost, St. John the Baptist, St. Lawrence, All Saints, and for all the apostles except St. Philip and St. James, and St. John the Evangelist.

From the above regulations, the following general dietary rules may be interpreted for colonial-era Spaniards:

General Dietary Rules for Days of the Week

- Sundays were never marked by fasting, and by abstinence only during Lent

- Fridays and Saturdays were always marked by abstinence, and also by fasting throughout Lent, during the four Ember Weeks, and on specific Vigil days.

- Thursdays were occasionally marked by abstinence on April 25, and also by fasting throughout Lent, and on specific Vigil days.

- Wednesdays were occasionally marked by abstinence on April 25, and always during the Minor Rogations, and were also marked by fasting throughout Lent, during the four Ember Weeks, and on specific Vigil days.

- Mondays and Tuesdays were occasionally marked by abstinence on April 25, and always during the Minor Rogations, and were also marked by fasting throughout Lent, and on specific Vigil days.