Indigenous Groups of Greater Spanish Florida

See below: Bibliography

See also: Mission Provinces / Peace Treaties / Present-Day Tribes

The region eventually assimilated into the expanding colonial system of Spanish Florida over the course of the 16th and 17th centuries was home to dozens of indigenous chiefdoms of varying size and configuration, and of varying degrees of autonomy, together consisting of many tens of thousands of Southeastern Indians whose ancestors had lived in this region since well before the end of the last Ice Age. In contrast, between 1513 and 1763, no more than 3,000 Spaniards and other outsiders from Europe, Africa, or other places in the Americas ever visited or resided at the same time within greater Spanish Florida, comprising therefore just the tiniest fraction (1/50 or less) of the original indigenous population of this region, despite ongoing native depopulation that eventually left that ratio far more balanced (with the number of immigrants actually exceeding refugees from the mission provinces by the early 18th century).

The region eventually assimilated into the expanding colonial system of Spanish Florida over the course of the 16th and 17th centuries was home to dozens of indigenous chiefdoms of varying size and configuration, and of varying degrees of autonomy, together consisting of many tens of thousands of Southeastern Indians whose ancestors had lived in this region since well before the end of the last Ice Age. In contrast, between 1513 and 1763, no more than 3,000 Spaniards and other outsiders from Europe, Africa, or other places in the Americas ever visited or resided at the same time within greater Spanish Florida, comprising therefore just the tiniest fraction (1/50 or less) of the original indigenous population of this region, despite ongoing native depopulation that eventually left that ratio far more balanced (with the number of immigrants actually exceeding refugees from the mission provinces by the early 18th century).

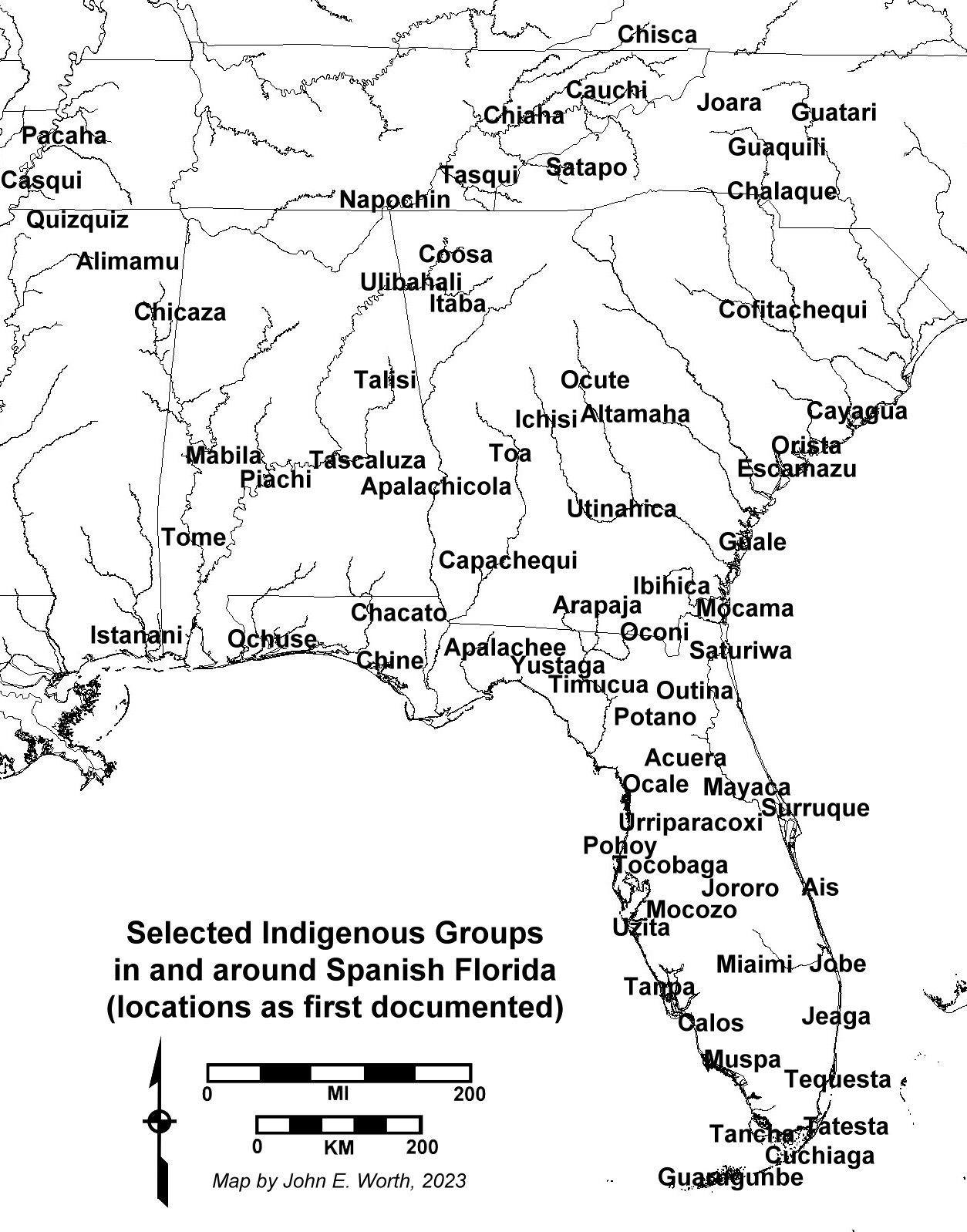

The map to the above right shows the names and rough locations of a number of selected indigenous groups within and around the area ultimately incorporated within Spanish Florida at its maximum extent (compare with the maps on the places page). Some of these names correspond to small-scale autonomous or subordinate chiefdoms, while others correspond to regional chiefdoms or confederacies, within which were several named small-scale chiefdoms. While nearly all these names also referred to individual communities, usually the local or regional administrative center, all were additionally accompanied by many subordinate or satellite communities in their immediate vicinity, each with their own individual names. Moreover, the names on the map only exist because they were visited or otherwise came into the knowledge of Spanish officials who recorded them in documentary form, which means the absence of names in many areas simply means there is no textual or cartographic evidence for the identity of any indigenous groups who lived there (and whose existence during this period can otherwise be demonstrated by archaeological evidence). For this reason, the map should only be taken as a selection of groups that we actually do have documentary evidence for, and an uneven selection at that.

It should be emphasized that Spanish Florida was successfully settled decades after the New Laws of 1542-1543 had been issued and implemented, within which Native American enslavement was specifically and explicitly outlawed, and indigenous groups and people in regions both previously and yet-to-be discovered were to be treated as vassals of the Spanish crown. While this obviously still meant that Spain autonomously exerted claim to New World territories and their indigenous inhabitants within their expanding colonial dominion, it nonetheless resulted in a very different approach to colonization and interaction with Native groups. From that point onward (and following the brutal expedition of Hernando de Soto between 1539 and 1543), Spanish colonial strategies in Florida were more about negotiated assimilation rather than forcible conquest. Explicit orders were issued banning the seizure of property or the appropriation of labor without payment, and Christian conversion took on an increasingly important role in actual practice (though it had always been a stated goal).

As Spanish Florida grew outward from its first successful colonial town at St. Augustine, a number of local and regional chiefdoms were ultimately assimilated into a small number of Franciscan mission "provinces," that seem to correspond to existing indigenous chiefdoms, or to what might be characterized as confederacies or alliances between smaller chiefdoms (with linguistic and other cultural ties). While some of these provincial entities clearly incorporated what had previously been independent or autonomous chiefdoms (particularly in the immediate environs of St. Augustine, where longer interactions with Spanish and earlier French colonists seem to have left many communities heavily depopulated, due in part to epidemic disease and early warfare), the configuration and composition of these mission provinces nonetheless provide a useful framework to understand the range of indigenous groups that ultimately formed the bulk of the multi-ethnic population of colonial Spanish Florida.

Toward the end of Florida's First Spanish Period, the practice of penning formal peace treaties seems to have been adopted by Spanish authorities, and I have included my own transcriptions and translations of several of these on this web page.

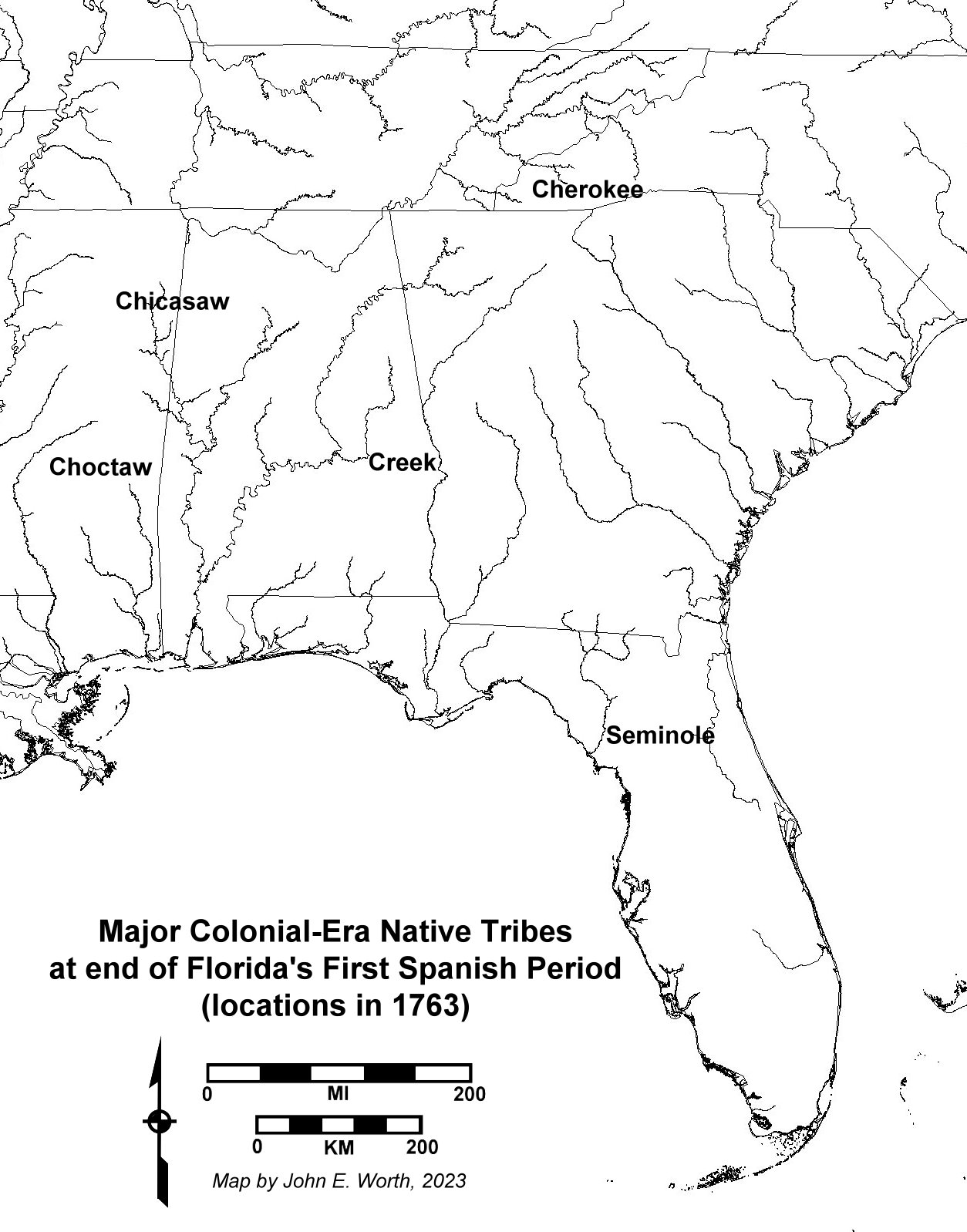

It should also be noted that even though the only native group originally indigenous to Spanish Florida that is currently known to have survived to the present day is the Apalachee of Louisiana, who are currently in two divisions, the Talimali Band of Apalachee Indians and the Apalachee Indians of the Talimali Band, there are many other recognized tribal groups across the Southeast and beyond who descend from the native peoples who neighbored Spanish Florida, and who still exist today. Most of these descend from the handful of colonial-era tribes that coalesced in specific locations in the interior from the surviving remnants of many of the indigenous groups shown in the map above, and survived by adapting to the rapidly-changing colonial borderlands between Spanish, English, and French forces surrounding them. By the mid-17th century, part of this successful adaptation meant becoming commercial slave-raiders for the English traders of Virginia and Carolina, growing in power and territorial scope by conducting increasingly aggressive slave raids against unallied indigenous groups across the Florida peninsula and the rest of the Southeast. The collapse and withdrawal of the missionized groups from their original homelands in Spanish Florida was eventually followed by the relocation of such groups into the then-vacant territory, as was the case with Creeks who ultimately displaced Florida's indigenous people and settled in the conquered lands of the groups they had previously enslaved. These immigrant groups eventually came to be known collectively as the Seminole, who were later pushed even farther south into the Florida peninsula during the American territorial period (see map to the right showing the core locations of remaining groups in 1763), and whose descendants still live in South Florida and Oklahoma as branches of the Seminole and Miccosukee tribes (see links to their homepages on my Present-Day Tribes page).

It should also be noted that even though the only native group originally indigenous to Spanish Florida that is currently known to have survived to the present day is the Apalachee of Louisiana, who are currently in two divisions, the Talimali Band of Apalachee Indians and the Apalachee Indians of the Talimali Band, there are many other recognized tribal groups across the Southeast and beyond who descend from the native peoples who neighbored Spanish Florida, and who still exist today. Most of these descend from the handful of colonial-era tribes that coalesced in specific locations in the interior from the surviving remnants of many of the indigenous groups shown in the map above, and survived by adapting to the rapidly-changing colonial borderlands between Spanish, English, and French forces surrounding them. By the mid-17th century, part of this successful adaptation meant becoming commercial slave-raiders for the English traders of Virginia and Carolina, growing in power and territorial scope by conducting increasingly aggressive slave raids against unallied indigenous groups across the Florida peninsula and the rest of the Southeast. The collapse and withdrawal of the missionized groups from their original homelands in Spanish Florida was eventually followed by the relocation of such groups into the then-vacant territory, as was the case with Creeks who ultimately displaced Florida's indigenous people and settled in the conquered lands of the groups they had previously enslaved. These immigrant groups eventually came to be known collectively as the Seminole, who were later pushed even farther south into the Florida peninsula during the American territorial period (see map to the right showing the core locations of remaining groups in 1763), and whose descendants still live in South Florida and Oklahoma as branches of the Seminole and Miccosukee tribes (see links to their homepages on my Present-Day Tribes page).

A bibliography of selected books on Southeastern Indians is provided below for those who wish to learn more about the subject.

Selected Books on Southeastern Indians

The books below are just a selection of useful sources, and include "classic" books that are available freely online, as well as modern books that are normally still under copyright.Famous Early Imagery

Bry, Theodor de

1590 Wunderbarliche, doch warhafftige Erklärung, von der Gelegenheit vnd Sitten der Wilden in Virginia, [1620 version here]

Le Moyne de Moruges, Jacques, and Theodor de Bry

1591Brevis narratio eorvm qvæ in Florida Americæ provi̇cia Gallis acciderunt, by Jacques Le Moyne de Morgues and Theodor de Bry (Frankfort : J. Wechel, 1591). [high-res engraving scan collections also in black and white here and in color here]

"Classic" Books

Crane, Verner

1928 The Southern Frontier, 1670-1732. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press.

Hodge, Frederick Webb

1907-1910 Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office.

MacCauley, Clay

1880 The Seminole Indians of Florida. Fifth Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, 1883-1884. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office (pp. 468-531).

Mooney, James

1900 Myths of the Cherokee. Nineteenth Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, 1897-1898. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office.

Speck, Frank G.

1909 Ethnology of the Yuchi Indians. Philadelphia: The University Museum.

Swanton, John R.

1911 Indian Tribes of the Lower Mississippi Valley and Adjacent Coast of the Gulf of Mexico. Bulletin 43, Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office.

1922 Early History of the Creek Indians and Their Neighbors. Bulletin 73, Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office.

1929 Myths and Tales of the Southeastern Indians. Bulletin 88, Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office.

1931 Source Material for the Social and Ceremonial Life of the Choctaw Indians. Bulletin 103, Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office.

1946 The Indians of the Southeastern United States. Bulletin 137, Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office.

Modern Books

Ethridge, Robbie

2003 Creek Country: The Creek Indians and Their World. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

2010 From Chicaza to Chickasaw: The European Invasion and the Transformation of the Mississippian World, 1540-1715. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Ethridge, Robbie, and Charles Hudson (editors)

2002 The Transformation of the Southeastern Indians, 1540-1760. Oxford: University Press of Mississippi.

Ethridge, Robbie, and Sherri M. Shuck-Hall (editors)

2009 Mapping the Mississippian Shatter Zone: The Colonial Indian Slave Trade and Regional Instability in the American South. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Hahn, Stephen C.

2014 The Invention of the Creek Nation, 1670-1763. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Hann, John H.

1988 Apalachee: The Land Between the Rivers. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

1991 Missions to the Calusa. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

1996 A History of the Timucua Indians and Missions. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

1998 The Apalachee Indians and Mission San Luis. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

2003 Indians of Central and South Florida, 1513-1763. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

2006 The Native American World Beyond Apalachee. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

Hudson, Charles M.

1971 Red White and Black Symposium on Indians in the Old South. Athens: University of Georgia Press.

1975 Four Centuries of Southern Indians. Athens: University of Georgia Press.

1976 The Southeastern Indians. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press.

1985 Ethnology of the Southeastern Indians: A Source Book. New York: Garland Publishing, Inc.

Hudson, Charles, and Carmen Chaves Tesser (editors)

1989 The Forgotten Centuries: Indians and Europeans in the American South, 1521-1704. Athens: University of Georgia Press.

McEwan, Bonnie G. (editor)

2000 Indians of the Greater Southeast: Historical Archaeology and Ethnohistory. Gainesville: University Press of Florida (ISBN 978-0813020860) [borrowable online for 1-hour intervals here]

Milanich, Jerald T.

1995 Florida Indians and the Invasion from Europe. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

1996 The Timucua. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishers Ltd.

1999 Laboring in the Fields of the Lord: Spanish Missions and Southeastern Indians. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Milanich, Jerald T., and Charles Hudson

1993 Hernando de Soto and the Indians of Florida. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

Pluckhahn, Thomas J., and Robbie Ethridge (editors)

2006 Light on the Path: The Anthropology and History of the Southeastern Indians. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press.

Sturtevant, William C., and Raymond D. Fogelson (editors)

2004 Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 14: The Southeast. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Williams, Walter L. (editor)

1979 Southeastern Indians since the Removal Era. Athens: University of Georgia Press.

Worth, John E.

1995 The Struggle for the Georgia Coast: An Eighteenth-Century Spanish Retrospective on Guale and Mocama. Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History, Number 75. University of Georgia Press, Athens.

1998 The Timucuan Chiefdoms of Spanish Florida, Volume I: Assimilation, Volume II: Resistance and Destruction. University Press of Florida, Gainesville.

2014 Discovering Florida: First-Contact Narratives of Spanish Expeditions along the Lower Gulf Coast. University Press of Florida, Gainesville.

Wright, J. Leitch, Jr.

1981 The Only Land They Knew: American Indians in the Old South. New York: The Free Press.

1986 Creeks & Seminoles: The Destruction and Regeneration of the Muscogulge People. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.